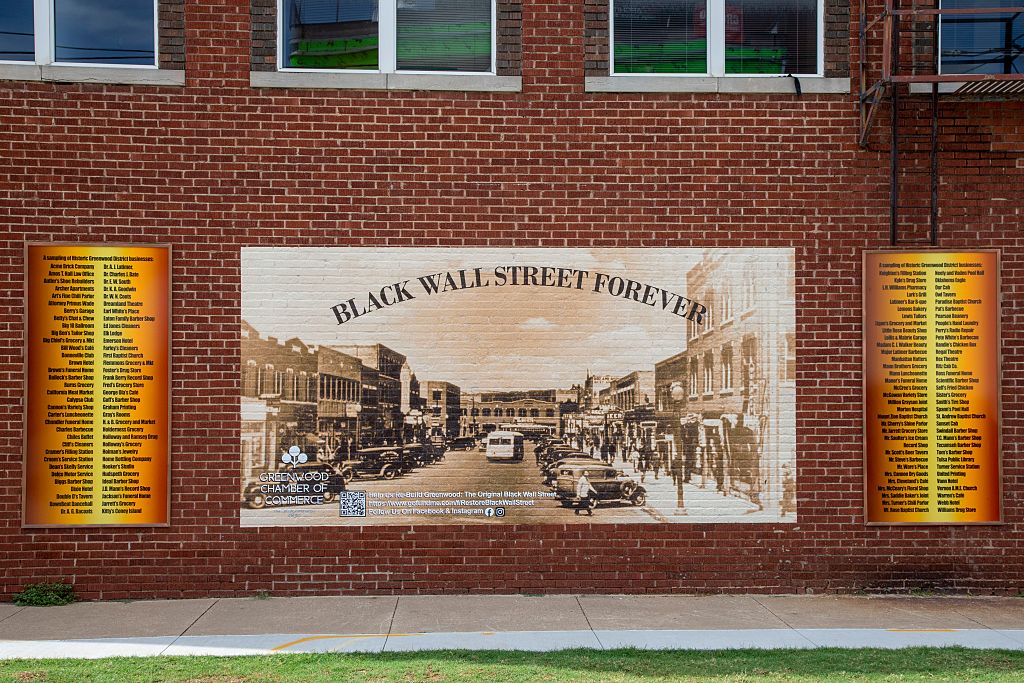

The campaign to bring restitution and repair to the damage done to the Black community of Tulsa, Oklahoma, continues, as the city’s mayor has unveiled a proposal to redress the century-old atrocity. The centerpiece of Mayor Monroe Nichols’ new plan is a privately funded trust that he plans to use to raise over $100 million for the redevelopment of the city’s “Black Wall Street.”

‘Road to Repair’ Tulsa’s Greenwood District

Nichols recently debuted his Road to Repair plan for Tulsa’s Greenwood District, the once-thriving Black neighborhood that was destroyed in a 1921 racist massacre. Nichols, the city’s first Black mayor, announced details of the plan during a ceremony commemorating the first Tulsa Race Massacre Observance Day. Nichols plans to establish a private Greenwood Trust and raise $105 million by June 2026, the 105th anniversary of Greenwood’s destruction. The money placed in the trust, as well as the salary of its executive director, would come from private sources and thus not require public approval.

The trust would not provide individual cash reparations payments to the last survivors of the Tulsa massacre or their descendants; instead, it would be used to revitalize the Greenwood area. The majority of the money, $60 million, would be dedicated to cultural preservation, focused on projects such as building renovations. Another $24 million would be allocated to a housing fund, and the remaining $21 million would be allocated to land development, education scholarships, and support for small businesses.

The 1921 Tulsa massacre destroyed the prosperous Greenwood District, also known as the city’s Black Wall Street, potentially killing hundreds of people and displacing more. Though largely ignored for decades, the massacre has received renewed national attention in recent years. Local and federal authorities have launched investigations into the atrocity, with Tulsa authorities exploring possible restitution for victims and their families, but these processes have yielded few results so far. Only two known survivors of the 1921 attack are still alive; they would not directly be paid through the current plan.

Providing restoration but not ‘reparations,’ per se

Outside of Tulsa, other cities and even states have explored providing reparations for injustices such as slavery, segregation and violence committed against Black people. In 2021, the city of Evanston, Illinois, became the first city to grant reparations. The state of California has conducted an extensive process toward reparations, although the significant recommendations emerging from that process have yet to be authorized by the state’s government.

However, given the current political environment, in which programs and policies that protect or benefit Black people and other marginalized groups have come under fire, reparations programs face a more challenging climate. Nichols’ plan potentially avoids some of this pushback by relying on private rather than public funds and by avoiding the label “reparations.” Nichols acknowledges that “the fact that this lines up with a broader national conversation is a tough environment, but it doesn’t change the work we have to do.”

The damage done to Tulsa’s Black community has endured for over 100 years, and the campaign to redress this wrong has gone through multiple phases in recent years. But as the city is led by its first Black mayor, his Road to Repair plan may present a new avenue for addressing the wrongs done in Tulsa and reviving its Black Wall Street.