If you’re interested in sharing your opinion on any cultural, political or personal topic, create an account here and check out our how-to post to learn more.

Opinions are the writer’s own and not those of Blavity's.

____

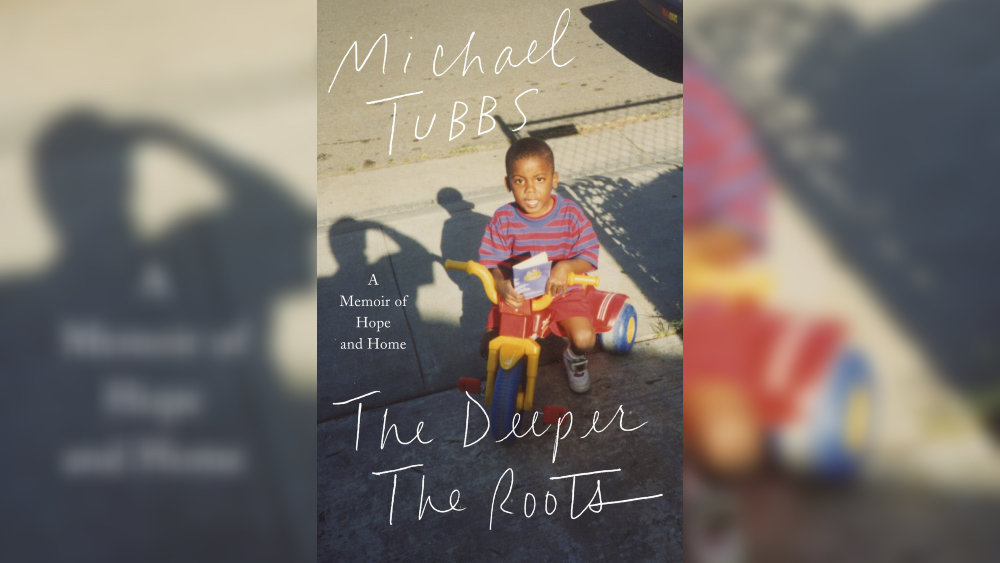

The following is an excerpt from chapter two of Michael Tubbs' new memoir, ‘The Deeper the Roots.’

____

My new friends at Lakeside invited me over their houses, and it was the first time I saw how well-off people lived. Nice, big, houses. Pools in the backyards. Lots of trees and manicured lawns. A whole other side of Stockton. A whole other world, really. In these castles, in between ducking defenders to score on the basketball court, I was constantly dodging questions from my friends’ parents. “What does your mom do, Michael?” It was always posed with a faintly accusatory tone. “I don’t know,” was my favorite refrain. That answer generally impeded progression to “What does your dad do?” Even when I didn’t answer their questions, I learned that some of these parents were ready to share their opinions and judgments with me.

At a week long science camp, nervous in line for a rock climbing wall, I sang to myself absentmindedly a song mom and I listened to at home, featuring Snoop Dogg and called “Wrong Idea.” “I want the world to see I’m a gangsta,” I mumbled. Unexpectedly, a chaperone on the trip went out of her way to make sure that knew she agreed. “That’s right,” she said. “You’re nothing but a little gangster.”

I knew people like her were trying to decide if I could actually belong in their world. The school dress code didn’t help. It called for collared shirts and khakis from Nordstrom, and my mom could only afford four shirts — yet we could only get to the laundromat on weekends. I did my best to keep my shirts clean for reuse during the week, but I was messy and not terribly conscientious. On the occasions when my shirts were too soiled to be worn again, I had to borrow one of Shaleeka’s, which, because they were girl’s shirts, had a ruffled collar. When a classmate grabbed my collar and informed the class that “MT is wearing a girls shirt!” I found myself repeating the laundry story in the principal’s office, having unleashed on the kid about his bad grades and ugly shoes.

The discrepancies between what I saw at my house and what I saw at my friends’ houses — and sometimes my own weird shirts — made me super competitive in the classroom. I had to be the best, period. I especially relished when I knew I had done better than classmates whose parents contributed heavily to their work. “Wait, didn’t your mom help you with that? How many did you miss? You missed three? Isn’t your mom a lawyer? I missed zero,” I yelled across class one day as the teacher handed back our graded work. “Michael,” my teacher warned. “What? I’m just saying.” And boom, I was kicked out of class. Again. For being disruptive. For talking back. For being defiant. I had a love-hate relationship with all of my teachers. Love for those that viewed me as a child to cultivate and challenge, and hate for those who viewed me as something that needed to be controlled. Mrs. Carter, my 6th grade teacher, got me; she would have me grade other students’ work or give me extra work to do. She’d call me up to her desk and challenge me with questions, or with middle-school textbooks to keep me occupied and not make my classmates laugh. Other teachers would say only that I was a “distraction,” not noticing that I was bored because I had finished the work and needed something to do. One teacher threatened to retire because I was in her class. I loved class when I was allowed to remain in it. I was quick to raise my hand, to ask questions, to not take things at face value, and willing to correct a teacher if a fact was wrong. I guess that rubbed some of my teachers the wrong way, and I was often sent to the office or forced to sit in the hallway outside. The break from the monotony of class, however, freed me to move at my own pace and to read ahead and let my mind wander.

My moms explained to me before and after inevitable parent-teacher conferences that some teachers didn’t like to be challenged in front of the class, or weren’t used to a student like me, and that I would need to be more measured. I didn’t listen; I had a growing chip on my shoulder. A paradox was becoming apparent: I was always on the Principal’s Honor Roll for having straight As and also was almost always in the Principal’s office. I didn’t have the language then, but I had a latent suspicion that it had something to do with being one of the few black students at Lakeside. I noticed how I was constantly kicked out for “defiance,” doing things my classmates were allowed to do without reprimand. I noticed that I saw most of the students who looked like me in the office, rather than on stage with me during the academic awards ceremonies. I noticed how my school community looked different than my church and home community. The only thing in my neighborhood that reminded me of my teachers were the cops that patrolled our streets. My sense of injustice wasn’t always 100% accurate. Towards the end of my sixth grade year, I competed in the regional Math Olympics. I knew I was good at math — Aunt Tasha had convinced the principal to allow me to take a higher grade in the subject, along with one other student whose father was a university math professor. So when it was announced that I didn’t even place in the contest, I knew there was some conspiracy. I had been cheated. I went to my mom and Tasha and tearfully pleaded my case. They believed in me and demanded to see the test. They looked and looked again.

Literally, I just had a lot of wrong answers. I had lost, but in retrospect, I won. I had fearless advocates who believed I was worth fighting for, no matter what.

____

Michael Tubbs is the former mayor of Stockton, California — city's first Black mayor and the country's youngest-ever major city mayor at age 26.