If you’re interested in sharing your opinion on any cultural, political or personal topic, create an account here and check out our how-to post to learn more.

____

“Ubuntu is an ideology!” he railed across the room. Tensions seemed to bubble to the surface. There was a spiritual battle for the moderator’s attention. You could feel in your bones that there was a lot at stake — if not from the cadence and tone of each interlocutor’s voice, definitely from the exchanges following the forum.

No, the conversations were not confined to formal settings. They spilled over into lunch and dinner — over tea and coffee; and in the evenings, over cigarettes, white wine and slow-brewed Tusker beer. I once came across two young men, not much older than myself, who were, from my perspective, shouting propositions back and forth at one another. Wanting to time my interjection just right, I eventually muscled up the courage to ask one of them in my distinctly Black American accent, “So, what language are y’all speakin, brotha?”

He smiled back at me, chuckled and said, “Dear brother, we were speaking about four different languages just now!”

He then paused for a second and acknowledged his interlocutor who, at that point, I could tell was obviously his close friend. “We tend do that kind of thing a lot,” he continued. “That’s the way you have to do philosophy here.”

I don’t know if it was after this exchange or before, but at some point, I began experiencing an incredible culture shock. This shock was accompanied by a lot of self-talk and reflection. In the thick of this inner-cognitive tribunal, I heard a voice with an unfamiliar character. This silent voice crept into my head and reminded me of a hard-to-stomach point that a Harvard-oriented philosopher like myself conveniently likes to pretend isn’t relevant: It whispered, “Darien, you’re not in Cambridge anymore.”

So where was I? I was in a land with more than 800 distinct natural language cultures. The fictions that we Westerners have cemented in our minds of the place we so lazily call “Africa” are and will continue to be the main barrier for persons from our standpoint for understanding what Barry Hallen calls “philosophy in the African context.”

Even myself, a Black American descendant of slaves from the rural south, wanted the Continent to be something for me. I wanted this vast social space to sit down, be quiet and let me define what it should be in relation to my experiences in the Diaspora. But what one quickly learns is that Africa submits to no one — not even to those who celebrate its name.

What I discovered instead during my time at the Third Biennial World African Philosophy Conference at the University of Dar es Salaam in Tanzania is that no one speaks for Africa. And to believe otherwise is to underestimate the lengths to which philosophizing in the African context is the main method by which the African experience is already speaking for itself.

The obvious point that I am trying to convey (I hope!) is that the Continent is not a monolith — no matter how much we in the West want or need it to be. At this conference, there was pride, there was respect, there was trust — but, above all, there was disagreement. Whether it was over the legitimacy and scope of the controversial Conversational School of Philosophy (CSP) movement spurred by Jonathan Chimakonam, the revolutionary anti neo-apartheid philosophy of South African philosopher Ndumiso Dladla, or the resurrection of the late Odera Oruka’s Sage Philosophy framework by his son Peter, there was a dynamic energy that enveloped the intellectual milieu and this energy could not be categorized, regimented or censored.

These contentions did not simply begin and end with the male gaze, either. Black woman philosophers from South Africa, such as Lindokuhle Gama, Lemogang Modisakeng, Nolwandle Lembethe, Motlatsi Khosi,Yolanda Mlungwana, Yoliswa Mlungwana and Nigerian American philosopher Rónké A. Òké, all represented the importance of not merely gender representation in philosophy on the Continent, but the significance of dismantling patriarchal structures in any cultural context.

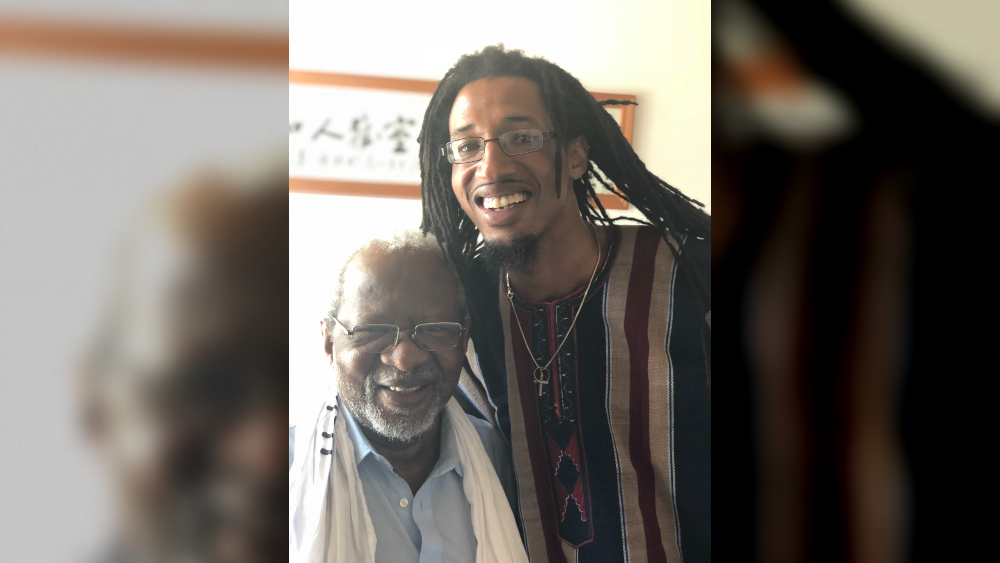

It should be acknowledged, too, that philosophy in the African context is not a novel phenomenon. Having the opportunity to meet and have personal conversations with revered intellectuals, such as Béninoise philosopher and statesman Paulin Hountondji and South African philosopher and compelling cultural critic Mogobe Bernard Ramose, revealed that this canon is as alive and well as many of its foundational figures.

Overall, the learning curve for me ended when I slowly began to realize that the African context did not need the categories that I came into the situation trying to impose on it. And, to do so was not only epistemically wrong and harmful. It was Western. It was hegemonic. It was, as I often describe in my own research and scholar-activism, extremely white-minded.

____

Darien Pollock is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Philosophy at Harvard

This piece was written in Nairobi, Kenya, on November 5, 2019.