If you’re interested in sharing your opinion on any cultural, political or personal topic, create an account here and check out our how-to post to learn more.

____

History is humanizing, yet the stories of so many important individuals are often left out.

Throughout my high school education, the only history I learned about Black people was during a crash course on the Civil Rights Movement in February, and when we talked about America’s history of slavery. As an impressionable young Black girl, I believed that was the extent of my history.

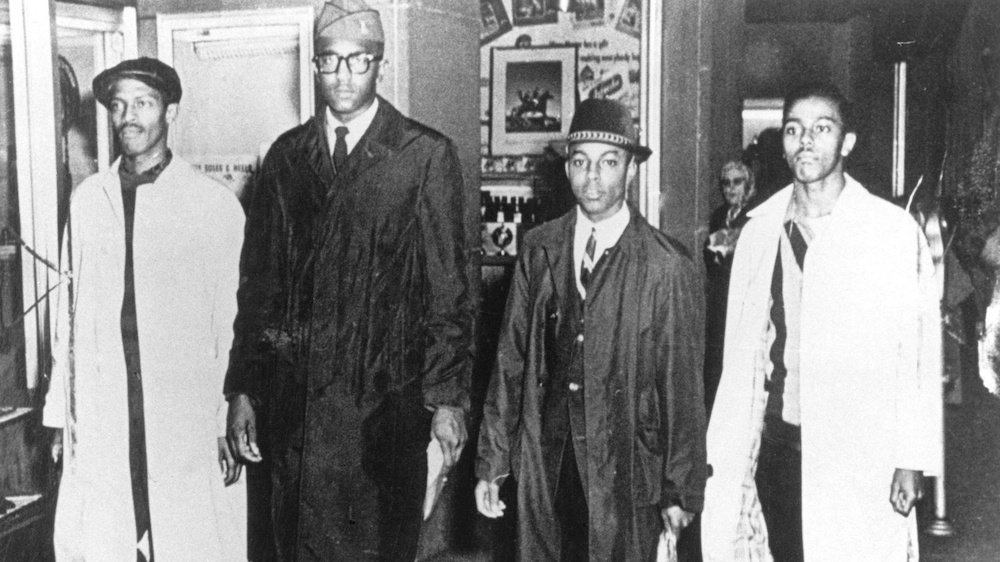

It wasn’t until a hot summer in Maryland, sitting in my grandparents’ yellow kitchen, that I learned about my own personal connection to history. My grandfather told me a story about how he had gone to college (at the HBCU North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University) with the Greensboro Four, a group of brave Black college students who started a lunch counter sit-in at Woolworth’s department store in the ‘60s. (The section of counter where they sat now lives in the Smithsonian.)

I also learned that contrary to what my teachers had taught me, the sit-in wasn’t peaceful — in fact, it was quite the opposite. While the Greensboro Four sat quietly, white counter-protestors spit at them, poured hot coffee on them and made threats on their lives. You can experience a sliver of what the protestors went through at The Center for Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta.

Despite the backlash they received, the protesters continued to demand equal treatment at that lunch counter for months. Their persistence eventually resulted in the integration of Woolworth’s, and their bravery inspired other student-led sit-ins in 13 states. I couldn’t believe my own grandparents went to college with them!

This personal connection to such a powerful moment in history sparked my journey to understand the intricacies of Black history — a subject which we barely scratch the surface of in our social studies classes. We talk about historical figureheads, but we avoid talking about the history of systemic racism, which continues to impact people of color to this day.

History is humanizing because without it, we cannot even begin to understand the lived experience of those around us. In my high school magnet program, which was predominantly composed of white and Asian American students, I witnessed firsthand the impact of an incomplete historical education on my peers.

I was called a “coconut” — brown on the outside and white on the inside — for being a high-performing Black student. I was told I would only get into a good school because of Affirmative Action — a stance that grossly misrepresents what the policy intends to do.

And many of the students in my class used the n-word casually with each other. During my junior year, I decided to confront them about their use of the racial slur.

Instead of an apology, I was met with multiple students defending their use of the n-word: It isn’t racist if we say it as a joke, and you’re being too angry and confrontational.

I had trouble finding the right words. How do I explain the issues with using the n-word to my white peers? How do I start unpacking how that word was used to dehumanize and delegitimize an entire race for hundreds of years?

I reported the incidents to my school, hoping that something would be done. Instead, they asked what I wanted the administration to do about it, and sent out an empty, school-wide email calling for the use of “inclusive language.”

Once I realized I would not receive any support from my school in addressing the slurs, I took matters into my own hands and founded DICCE, an organization that creates programming and curriculum for Gen Z that explores Diversity, Inclusion, Cultural Competency and Equity. Our team is composed of students from across the country, along with three adult advisors, representing an array of experience with DEI and anti-racism. In our curriculum, we strive to close the gap between history and the present-day, lived experience of marginalized people.

With support from Civics Unplugged, a civic social enterprise that empowers young people to build the future of American democracy, and the University of Kentucky, we began seeking resources that we could utilize to educate the next generation on the history of race.

Through the Made By Us coalition, a network of history and civics institutions that have joined forces to develop new tools and experiences to meet the needs of young people, we discovered the National African American History and Culture Museum and their collection of resources explaining the origins of race and how to be an anti-racist. These resources served as launch points for our deep dives into the origins of race science, breaking down these complex sociological concepts for high school students.

Learning a broader version of history is humanizing. We can’t create inclusive spaces until we understand the history of those around us, and we cannot begin to reform our institutions to be equitable and just until we understand how we got to where we are.

That means understanding the complex history of slavery and immigration, examining how we have reclassified race and determining how privilege has evolved over time. It also means asking the hard questions: Why are police officers incentivized to arrest more people? Why are there more Black people than any other race on death row? Why did our schools remain so segregated, even after Brown v. Board of Education?

The humanizing process starts when we look critically at history, and realize that the names and faces we see in history books are more than just ideas; they were and are real people who dared to make change happen.

For me, the process started in my grandparents’ kitchen in Maryland, when I heard the story of their friends, the Greensboro Four. I hope that for you and my peers, that process will start today.

Ask yourself the following: Are you hearing every perspective of a historical event? Who is writing the history you are learning? And most importantly, where can you go to hear from those whose voices have been silenced? The answers to these questions might invite a new perspective.