If you’re interested in sharing your opinion on any cultural, political or personal topic, create an account here and check out our how-to post to learn more.

____

Written by Jesse Milan Jr.

____

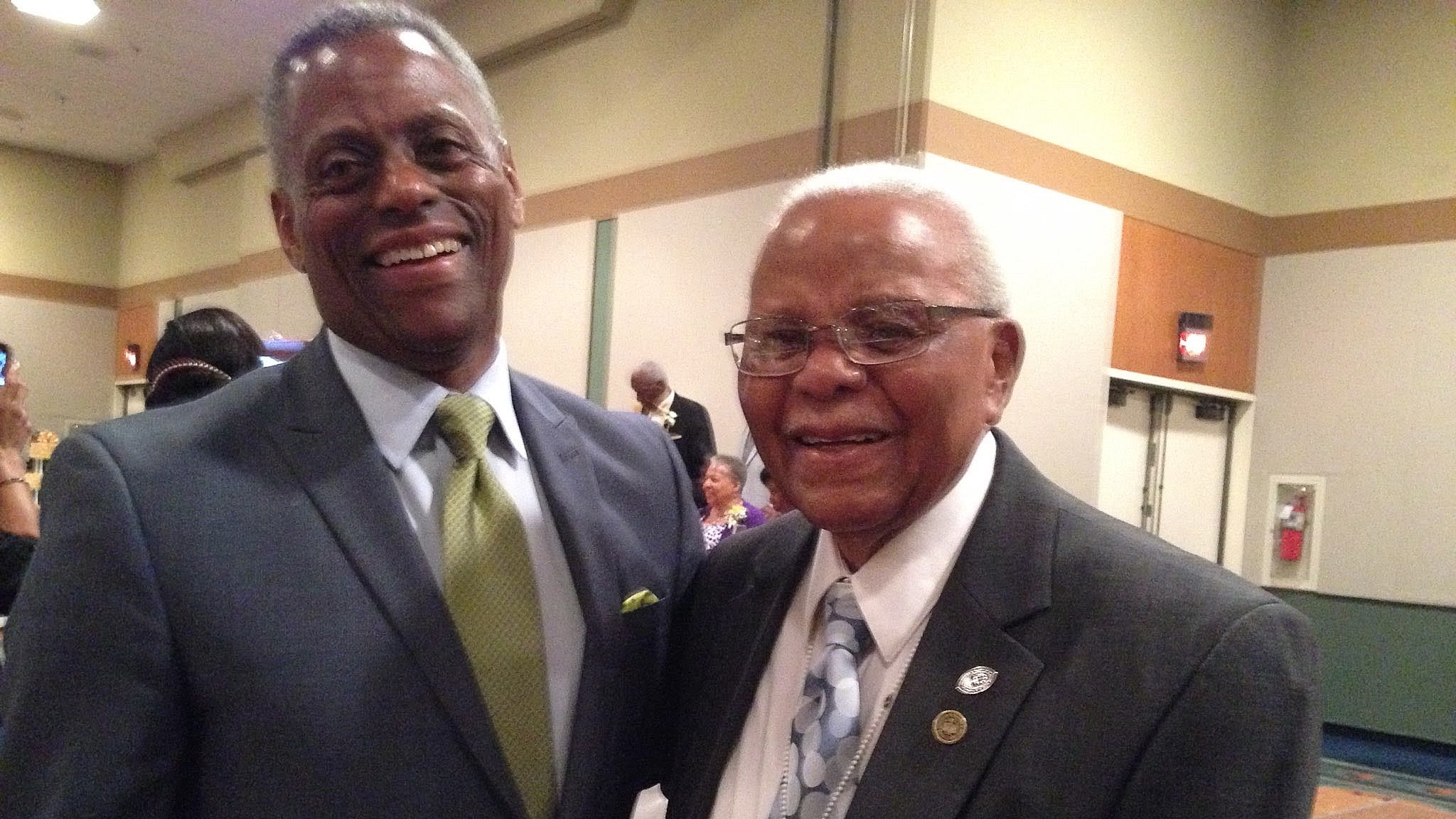

My father died on February 8, 2021. He was a civil rights leader, the state president of the NAACP and led the creation of the first integrated swimming pool in my home state of Kansas.

When going through my father’s dresser drawer — a treasure trove of his personal effects and our family’s history — I was stunned to find a copy of the first sermon I gave on HIV. I preached that sermon at a national faith event in 1992. Following the event, I mailed him a copy with a personal note. It was the first time I shared directly with him in a way that he would understand that I was living with HIV.

When those of us living with HIV come out about our status, our greatest fear is losing that which sustains us: our homes, our friends, our jobs and the love of our families. Telling someone our status holds risks that are hard to face, and even harder to bear. These were my fears as I mailed my father that sermon 30 years ago, and they are fears people still face today.

Indeed, I spoke recently with a gay Black man living with HIV who is 30 years my junior whose parents deeply wounded him by refusing to accept him. And I met recently with a straight Black man who has been living with HIV for more than 20 years and has still not told his family. There are so many more stories like these that could be told.

I am lucky. My father did not disown me, and he and my mother never stopped loving me and never stopped being proud that I was their child. If only all of us living with HIV could be so open and so loved.

I had lost my copy of the sermon. Finding it among my father’s possessions and rereading the note I wrote to him that he kept to the end of his life made me love Daddy even more. It reminded me how much he loved me. And by keeping the sermon and note among his family treasures, he made it very clear to me that our family history includes both his story and mine with HIV.

Black family histories are in every fiber of Black History. My story of acceptance is part of the Black historical narrative, but so too is the rejection and pain of those two men. Our HIV stories are a part of Black history. This is part of the reason National Black HIV/AIDS Awareness Day is set for February 7, in the midst of Black History Month.

But this awareness day is also important because our community has been and continues to be hit hard by the HIV epidemic. More than 40% of the people living with HIV in the United States are Black and 42% of new cases of HIV are among Black people.

Black people lag behind in our usage of preexposure prophylaxis, or PrEP. PrEP is a medicine that protects someone who does not have HIV from ever getting the virus. It’s one of the best tools we have for stopping the spread of HIV. But too few Black men and women are aware of or taking it.

Those of us who are Black and living with HIV are less likely to be on HIV treatment and reach an undetectable status. Reaching an undetectable status is one of the biggest goals for those of us living with HIV. It means the amount of virus in our bodies is so low it cannot be detected by lab tests. Reaching an undetectable status has critical health benefits and allows us to live long, healthy lives. But also undetectable equals untransmittable, or U=U. Someone with an undetectable viral load cannot pass the virus along to anyone else. Despite these personal and public health benefits, thousands of Black people with HIV are not reaching an undetectable status.

All of those statistics are true, not because we are somehow more susceptible to HIV or genetically predisposed to acquiring the virus, but because of racism, stigma around sexuality and sexual health, and barriers to health care. These realities are all part and parcel of the Black experience in the United States, and therefore HIV is very much part of Black History. Truly, HIV is among our people’s many struggles.

And for those of us who are Black and surviving and thriving with HIV, it is also among our victories to date. But for Black people still vulnerable to HIV and its stigma, illness and death are among our victories yet to be won. Through testing, HIV prevention and treatment, building our awareness, and reducing stigma we can end the HIV epidemic. Let’s stop HIV together.

____

Jesse Milan Jr. is the President and CEO at AIDS United.