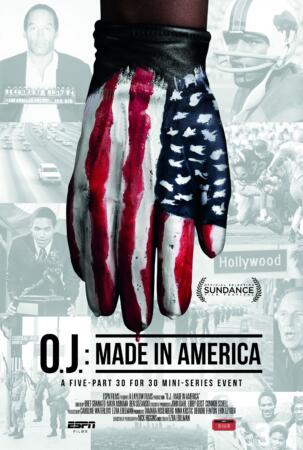

The landmark, comprehensive, even *epic* 7-hour “O. J.: Made in America” premieres at 9 p.m. tonight on ABC.

The year Orenthal James Simpson was acquitted of murdering his ex-wife Nicole Brown Simpson, and her friend Ron Goldman, I was entering Kindergarten. I vaguely remember the hoopla surrounding the trial, sitting on my father’s knee while he discussed it with his friends, or hovering around my mother and my aunts; my ears listening intently to “grown folks business”. The things that I heard at that time, I didn’t really grasp. As I grew older, especially as Simpson’s behavior became more publicly erratic leading up to his 2007 arrest and conviction, I formed my own opinions about the fallen man who in my eyes, was so obviously guilty of the heinous crimes. And yet for one moment in our country’s history, Simpson’s privilege without regard to his skin color let him slip through the system.

Though my generation has come to learn more about the egotistic football star and actor with projects like FX’s “The People v O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story”, it’s the moments leading up to the sensational trial that are absent from our imaginations. How did this affluent Black symbol living in this country during the ’90s get to this point?

Directed by ESPN’s “30 For 30” alum Ezra Edelman, “O.J.: Made In America” reaches back in time to find a stunningly handsome young running back from the San Francisco projects who would become The Man on USC’s lily white campus during the late 1960’s. During a time when the country was rife with racial tension and animosity, O.J. Simpson began seducing the public with his easy charm and football abilities, while simultaneously working to shed his blackness. Edelman takes a microscope to Simpson’s career and personal life, and then pans out, giving the viewer a sweeping scope of the racial climate of the United States and more specifically the migration of Black Americans to Los Angeles, California.

At the Museum of Moving Image last Thursday, I screened Parts 1&2 of “OJ: Made In America”, the first three hours of Edelman’s masterful five-part documentary saga. I found myself seduced and charmed by the magic of “The Juice”, while concurrently enraptured by the history of Black people living in L.A. from the mid-1960’s to the 1990’s. If you are ever going to watch anything on O.J. Simpson’s “O.J.: Made in America” is the project to see. The film looks well beyond the wholly ambitious athlete into the Watts riots, the killings of Eula Love and Latasha Harlins, the destruction of the apartments at 39th and Dalton and the beating of Rodney King. As much as this is a documentary on O.J., it’s one of the Black people living in Los Angeles during this time period, and a country that was able to create and sustain these polarizing worlds. It is perhaps one of the most compelling documentaries I’ve ever seen.

After the screening ended, Edelman sat down to chat about his two-year journey to complete the project, his narrative structure, and the things he left unsaid.

On Finding the Narrative Structure

As you know the story structure is always the hardest part. However from get-go, I knew that as much as I wanted to explore all of the terrain that had to do with O.J. in 1994, I also understood that anyone who was going to come to this story, is going to want some kind of understanding or some perspective in terms of how we got to the trial and to the verdict. That in many ways, has very little to do with O.J. So from jump, I was like, “OK, I’m going to tell O.J.’s story as best I can, but I also know that this is very much a story about Los Angeles and the LAPD.” At least from a jumping off standpoint, I knew enough about O.J. and that period in time where he became famous which was ’67, ’68 at the University of Southern California (USC). So from the beginning, I was fascinated by the juxtaposition of the Black kid who grew up in the projects in San Francisco, and arrives at USC in ’67. It’s a place that is very white, very elite, and very conservative. Also, it’s literally located within South L.A., and a year and a half before O.J. got there, the place had exploded in violence. That juxtaposition and knowing after those two years where O.J. went, the path that he took which was commercial super-stardom and becoming an NFL football player, I knew that these paths were the stories that led us to where we got in the trial. We had a beginning. Then it was, how do we carry through the story of L.A., while trying to maintain the narrative of the rest of O.J. as a character? Some of it is just gathering as much material as possible through archival footage and first person accounts, and some of it is in the editing. We had great editors and they did an incredible job.

On Starting at USC

You’re sort of hamstrung by the archival material that does or doesn’t exist, the sort of anecdotal material that you have. There are very few photographs of [O. J.] as a child and there is no footage of him as a child, so that makes that harder. We didn’t have his family to talk to about that time. But having said that, going back to this period of time where O.J. is going to USC in 1967 or even O.J. becoming well known as a football player in 1965 when he went to junior college in San Francisco. It was that concurrent story of him becoming this football star everyone knows, while no one knows what the people of Watts are going through, so they have to literally burn down their neighborhood to get attention. That was the juxtaposition of where the story begins versus where we are going later. So whether it’s the thirty-year story from 1965-1995 or the fifty-year story from 1965-2015, that was more where I was thinking.

On Not Getting Seduced By the Majesty That Was O.J. Simpson & Telling A Fair Story

I think that more so than almost anything I’ve ever done, I focused on fairness on a lot of levels, not just to O.J. but also to the police. I know that they do a really difficult job, so I knew I wanted to hear their experiences first hand, and not just assume the worst about everyone. From O.J.’s standpoint, it was about being fair to him, but it was almost just embracing the complexity of him. I think he’s sort of been reduced to the symbol of the trial. Therefore, it was so fundamental to the narrative and the story to be seduced by him all over again. It’s so important to see how beautiful he was as a football player and how graceful he was. It was important to see how beautiful he was as a man, to see how charming he was. You need to get to that place where you are in disbelief, and you’re saying, “That guy couldn’t have done that.” That’s essential to the story; you have to emotionally engage with him in the same way I think an audience has to emotionally engage with that history. The audience needs to know everything that happened with the LAPD and the Black community, and seeing the encyclical nature of an environment where these incidents happened. You can’t just start the story at 1994 and say, “By the way L.A. has been a really sh***y place to be if you’re a Black person when it comes to the police.” It’s sort of like, I need to live through this emotionally myself because you cannot empathize with the people you need to empathize with by the time you get to the next few hours of the story, and that was very important in terms of how I wanted to lay out the narrative. I really was making sure you connected with O.J. as a character, but also the rank and file people in the city of Los Angeles.

On The O.J. Simpson & Bill Cosby Analogy

Understanding what O.J.’s teammates and business partners felt, I think everyone felt that. Anyone who watched O.J. on television, or anyone who experienced him knows he brought us joy. We were connected to him in that way. So in some ways, we’re all complicit in having built this guy up to the person that he became. That also explains the shock that we all felt when we learned he was accused of murder, because to us, that just didn’t make sense. There are very few people who are like that. It’s why Bill Cosby is the extreme example. It’s not just what he did, but it’s what he represented, who he was, and what came out of his mouth. And, there was that added thing of the hypocrisy. So it’s always relative in terms of how these people affect us, and the place they hold in our culture, in terms of how destroyed we feel when we realize that wasn’t the reality.

On The Interviewing Process

What we found was that the people who had a very sort of specific relationship with O.J., like his teammates, or a finite time frame when they knew him, they need to keep it how it was. The people who were his teammates aren’t trying to demonize him. They say, “The guy who I knew at that time really was that guy.” It’s very place specific. They say, “That guy, couldn’t have done that.” That’s their truth across the map. There were people who were more willing to be forthcoming about what they went through in terms of feeling sort of burned by him. For example, Frank Olson who was the CEO of Hertz, you really felt like he took this guy under his wing and really helped him out. Then it was like, “What did I do?” People felt guilty that they never realized that all of this other stuff was going on. They felt like they had been had.

There was a huge reluctance on the part of a lot of people to sit down and participate. A lot of people in terms of this story have been beaten down by their exposure to the media in the past two decades. So trying to scale that wall and get behind it to say, “We have a different approach, we really have no agenda we just really want your experience talking about O.J., or Los Angeles, or the time period.” So a lot of people appreciated where we were coming from, and how much homework we had done. Having said that, we interviewed seventy-two people, and not that everyone was difficult to get into a chair, but it felt like it was a mini-battle that went on with everybody just to get to that point. So more than anything else, that was the most exhausting part of the process before you started to amass the material. There were of course people I would have liked to interview, Chris Darden (one of the prosecutors in the O.J. trial) he would have been the number one person I wanted. Certainly people in O.J.’s family, Marguerite (Simpson’s first wife), there are tons of people I knew I wanted to talk to, but frankly these are people I knew who never would talk.

On O.J. Simpson’s Refusal To Acknowledge His Blackness

When you hear him say, “I’m not Black, I’m O.J.”, that’s a very easy tipping off point. And yet at the same time, I found myself having a lot more empathy for him as a twenty-one year old kid who shows up at a place, and it’s like this world is foreign to him. He wanted to navigate just what was in front of him. He wanted to play football, and even if you want that, that’s a lot to deal with. None of his other teammates had to present themselves as a model athlete, or do interviews on campus, or what have you. And then, you have the “Justice League of Black Athletes” telling him to join them. That’s what it feels like when you see the 1968 LA Summit, it’s like, “Everyone is there except you O.J.” So yes, these athletes were on the right side of history, and what they were fighting for I agree with, but they were also incredibly strident in their rhetoric and what they were about. They were saying, “You need to join us, and if you don’t well, f**k you”. If I was twenty-one years old, my head would explode, and so in that way, the statement “I’m not Black, I’m O.J.” goes to far. It’s what he said, and based on what’s going to come out of his mouth going forward, that’s what he meant. However, I wanted to try to give him a little bit of a pass because it’s more complicated. Why is it so wrong if you’re just saying, “I’m trying to focus on this thing, I want to do this.”

On Sitting Down With NFL Hall Of Famer Jim Brown

When you’re doing a story about O.J. Simpson, especially considering what I was interested in, Jim Brown is at the top of the list. He is the model for O.J. in many ways, and he is the guy that O.J. diverged from. The problem was that Jim Brown is also a very complicated person when it came to what we were trying to do. Jim Brown had a trajectory where he was always more socially minded and responsible, but he’s also someone who has been accused of rape, and he’s gone to prison for domestic abuse. He’s had a history that is fraught, so I think when it comes to talking about O.J., he’s been very critical in the past about the choices that he has made, but when it comes to other parts of his life, it’s sort of those who live in glass houses. So I think he was very reluctant to participate. Having said that, I think what I primarily wanted to talk to him about, and what he’s in the movie to talk about, was the obligation and the movement of Black athletes at that time. We chatted about why a guy like him with all of the money, power, and celebrity that he had as a Black athlete, why he still felt the passion and the responsibility to be engaged with the movement. And because he really was the forerunner to O.J., he was a necessary voice. O.J. was sort of Jim Brown lite in many ways.

On The Things Left Unsaid

The thing about making a movie that is seven hours and forty-five minutes long is that, if there was something that I loved it’s in the movie. There were ideas that I wanted to put in the movie that I didn’t have the material for. I would have loved to have talked about the rumors surrounding O.J.’s cocaine use, and the role that it played in his life both as a football player in Buffalo, NY, but also in the ‘80s and how that affected who he was. That’s something I would have loved to discuss as part of his lifestyle, but I didn’t have the narrative justification or material to do that. The only scene that we cut from the movie was a discussion about O.J possibly having CTE (Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy). We cut it out because first of all it’s one hundred percent speculative, you cannot examine people’s brains until they are deceased. Secondly, if you know the symptoms of CTE, in terms of what happens, allegations of abuse go back with O.J. as far back as his relationship with his first wife. Trying to prove or say, “Of course, he played football he got hit a lot in the head that’s why he’s violent.” I thought, “No, that’s a cop out.” And, I think it gives O.J. a pass for all of his sociopathic narcissistic tendencies. I felt that was not the right thing to do but, it’s also interesting because he might have CTE.

On Saturday June 11th, the first of five episodes of “O.J.: Made In America” will air at 9 ET before the series heads to ESPN. If you are in the NYC or LA areas you can watch all 464-minutes in one sitting at the movie theater.

Aramide A Tinubu has her Master’s in Film Studies from Columbia University. She wrote her thesis on Black Girlhood and Parental Loss in Contemporary Black American Cinema. She’s a cinephile, bookworm, blogger, and NYU + Columbia University alum. You can read her blog at: www.chocolategirlinthecity.com or tweet her @midnightrami