Luxury is about image. This should come as no surprise. We understand this implicitly; every season brands produce new images to consume alongside their new collections. We indulge in the fantasy of the worlds that these pictures create. In a world that is increasingly splintered and difficult to understand, images, by contrast, are pitched at our desires: For power and prestige, for sex and money. We crave authenticity and history and pine for authority and pleasure. And in our world, still defined by dynamics set in motion at the outset of European colonialism, these desirable qualities are inextricably linked to our very understanding of Europe and the West more globally. To sell luxury is to sell a lifestyle, one often synonymous with ideas of “Frenchness’ (as embodied by the ominous and oft-referenced “French perspective”) and even today fashion editors the world over include mentions of brands’ Italian heritage, framing every new collection in relation to the companies’ nationalities and histories.

And, of course, in examining the actual histories of metropoles like Paris and London, it makes sense that these cities, the cherished and guarded capitals of the Western world, within whose cobbled streets and marbled facades is written the very history of colonial plunder, should be revered as the cultural capitals of that same Western World. Presumably, creativity and time-laden artisanship know no bounds in places unfettered by endemic want or systemic scarcity. And so the real history of the fabulous jeweled embroideries and supple leather saddle bags of France and England is also the history of the jeweled thrones from which ships and plots were launched, and the saddle bags toted along as people were captured and historical trajectories changed forever. Today, fashion overlooks the politics of the images it creates; casually and remorselessly appropriating styles, developing concepts rooted in problematic stereotypes, and most often, ignoring black creativity, ingenuity and beauty all together.

At the same time, it’s obvious that fashion’s visual content is also immediately political; every image presents the author’s own understanding of beauty which, in turn, has long influenced the way we conceive of and interact with the people we meet throughout our lives. Early modern philosopher Immanuel Kant, for example, justified European colonialism by arguing that even slaves who had been freed had never produced anything of comparable beauty to their European counterparts. In turn, beauty has been long recognized as a domain of political influence (the black is beautiful movement emerged at precisely the moment that Stokely Carmichael called for Black Power), and black artists from a variety of disciplines and eras have long embraced the political potential of depicting themselves beautifully, often in defiance of Western norms.

This, I believe, is the function of black art. It offers us a chance to reimagine ourselves, our bodies, our histories and our futures.

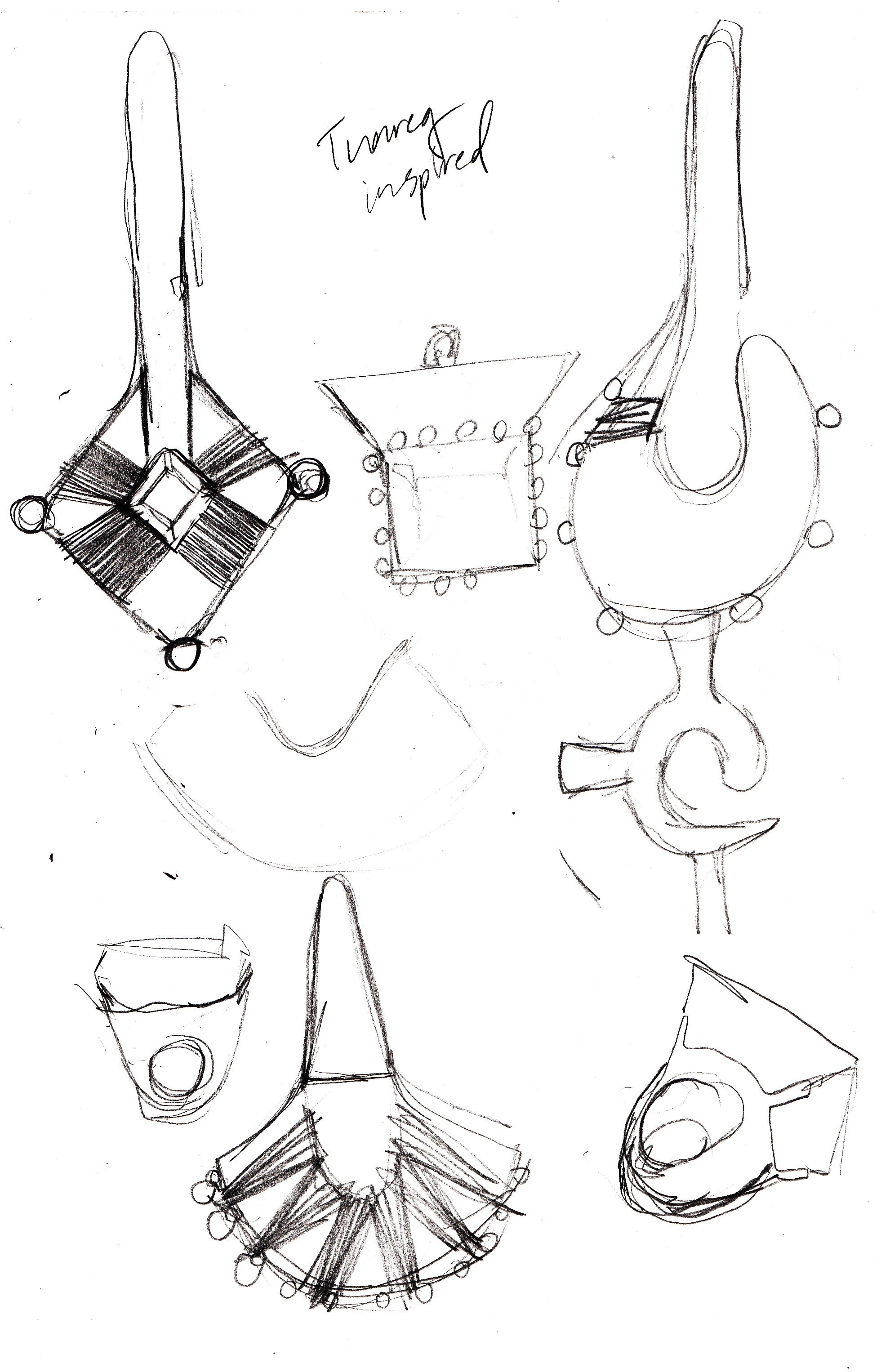

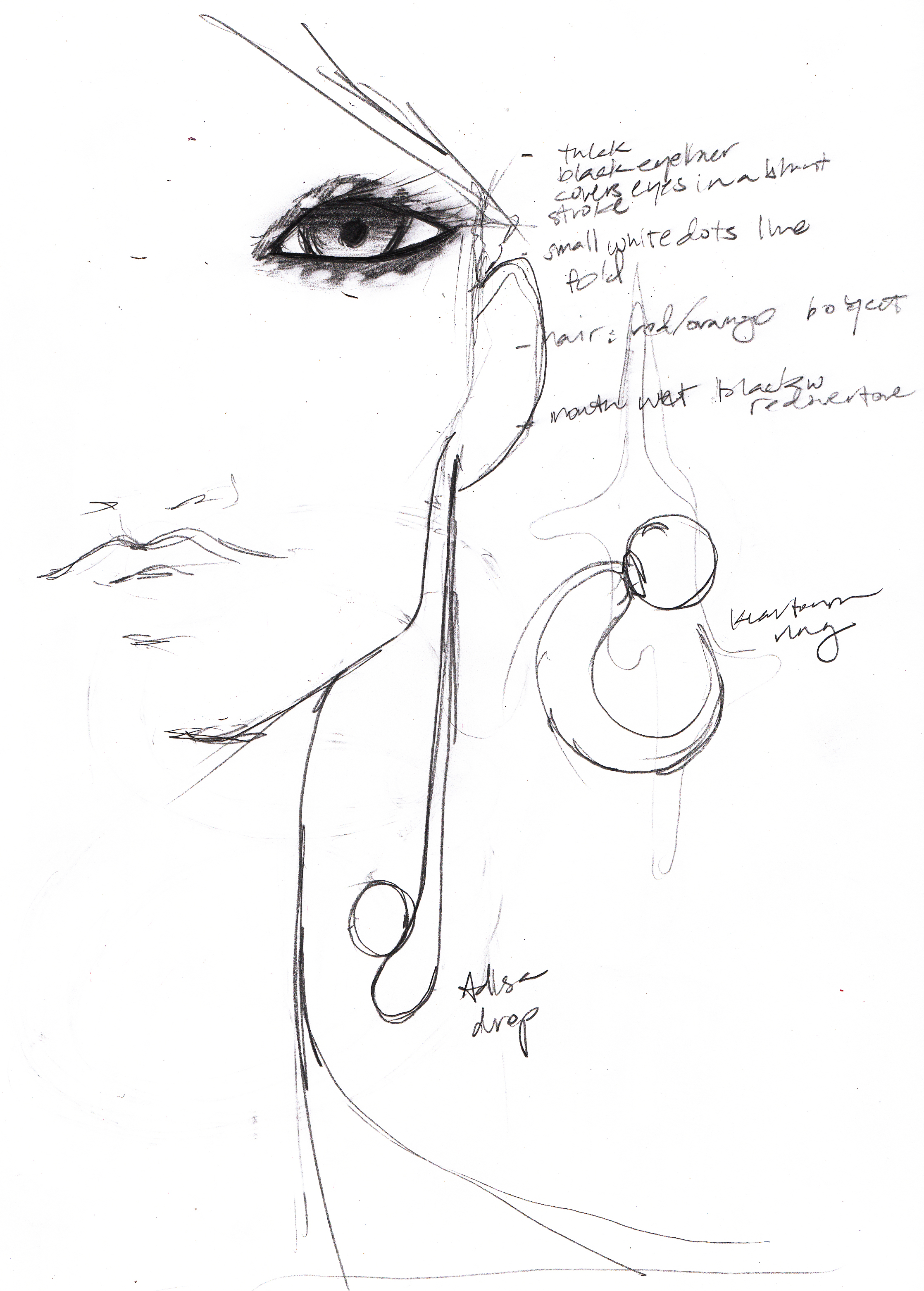

It stands in the maelstrom of imagery, a fort in the storm, a window to a new possibility for oneself and one’s own community. Artists such as Nina Simone, Kehinde Wiley, Kerry James Marshall and James Baldwin, all of whom I count among my inspirations, undertook their work with the goal of reexamining their own place in the world. On a personal level, KHIRY is my opportunity to do the same; to reexamine my own history, to find myself, my body, my power and my voice, in the historical record. It is a chance to see my own origins on my own terms, and to champion the beauty and distinction of that heritage.

Ultimately, the process of diaspora is one of spreading; on slave ships and airplanes African people have come into uneasy contact with the broader world. But even as our paths have diverged, the roots of traditions lost and demeaned lay present still throughout the diaspora. In innumerable songs and countless dances, the same hips wind, the same legs bend and reach. In Bahia and Brooklyn, St. Kitts and St. Louis, the same voices climb and the same rhythm pounds, with the insistence of a culture that will not be washed away.

KHIRY is an opportunity to center the black body in the reexamination of this cultural past, and in the struggle to define our collective future. It is the opportunity to take a speculative look at the imagery that surrounds us, and to offer a new vision of blackness; one informed by a truth I’m still searching for, but which I can also immediately grasp. And now, as I present these images, I recognize the soft power that has always existed in luxury; the dark allure of it, its ability to manipulate desire, to impose a perspective onto the world, and to communicate a truth. Perhaps, as countless artists and philosophers have found before, there is some small revolution in that.

Follow Jameel Mohammed, Creative Director of Khiry, on Instagram @khiryofficial. And check out the brand on M’oda ‘Operandi.

Loving Blavity? Sign up for our daily newsletter here.