In many Black families, grief is something they live through but rarely talk about. The rituals are shared experience for most families. They gather for services, prepare food for the repast, share stories that honor the departed, and return to life’s responsibilities as if nothing has shifted. Beneath that rhythm, however, pain often goes unacknowledged and emotional vulnerability is practically taboo. This silence didn’t come from nowhere. It is an inheritance passed down from generation to generation. Black people have been conditioned to “keep going” in the face of loss, no matter how hard it may hurt. For many, particularly Black women, grief has been internalized, carried in the body, and passed on like a family heirloom.

Chantal Rochelle knows this silence intimately. When her mother died in 2019, Rochelle found herself navigating her own grief while watching her three-year-old niece wrestle with questions no one seemed prepared to answer. Once she asked where her grandmother went, Rochelle realized her niece’s curiosity was an opportunity to break a generational chain.

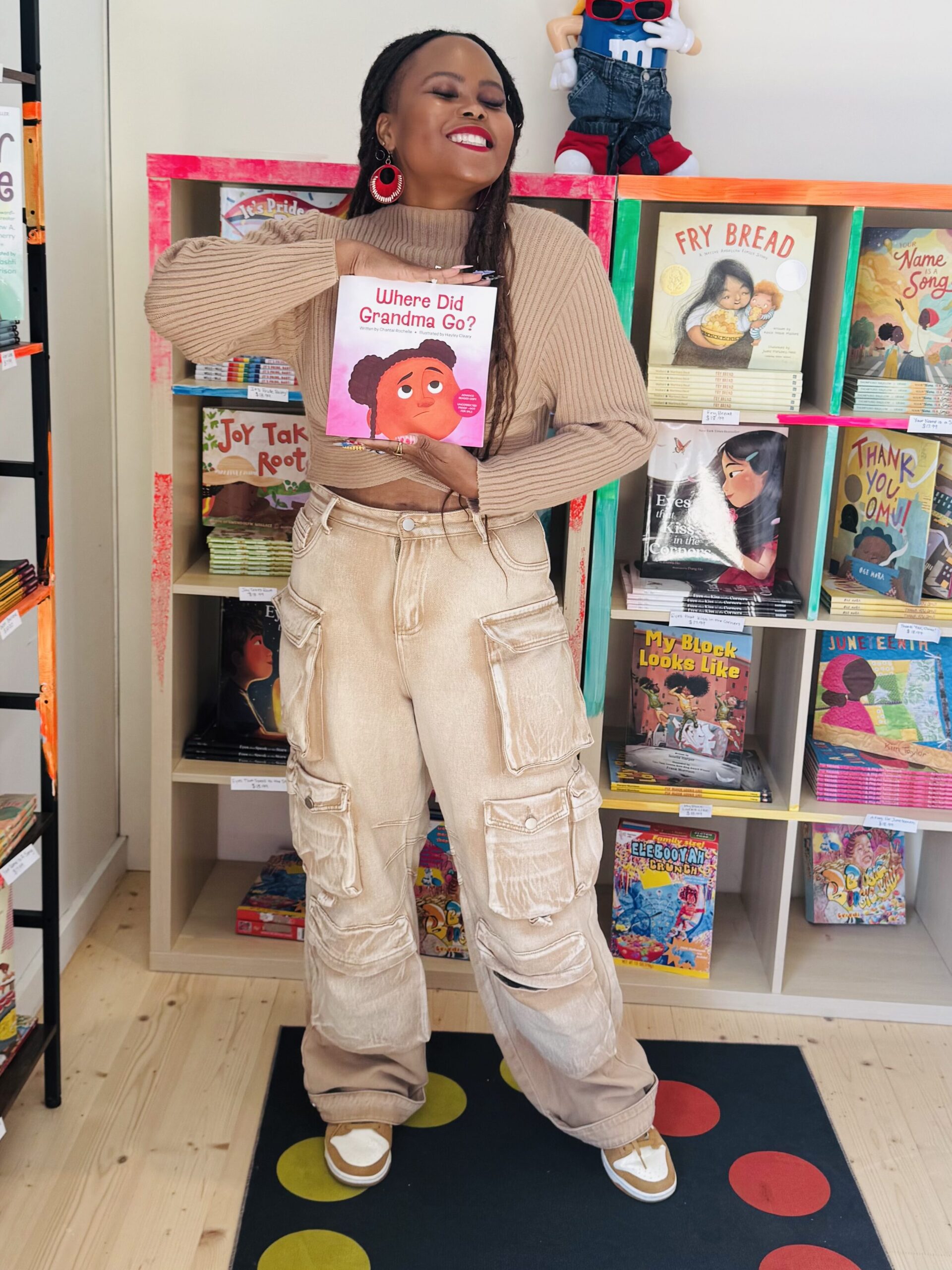

Chantal Rochelle Putting Purpose Behind Healing

Her debut children’s book, “Where Did Grandma Go?,” grew from that moment. It’s a tender, rhyming story designed to help children process loss while challenging the cultural norm that grief should be endured quietly and without conversation. Rochelle wanted to create something that honored her niece’s insistence on answers and, in doing so, offered permission for families to sit in both sorrow and joy at the same time.

“In my family, when someone died, it was all about logistics—planning the funeral, setting up the repast, making sure the food was good,” Rochelle recalled to 21Ninety. “But nobody ever asked, ‘Are you okay? How are you feeling?’”

That absence of acknowledgment mirrored what she saw growing up, where elders modeled stoicism as survival. Grief wasn’t something to express; it was something to push past. But children don’t follow those rules. Rochelle’s niece wanted honesty and connection. In her persistence, Rochelle saw the possibility of rewriting the narrative. Instead of shielding children from death, “Where Did Grandma Go?,” meets them where they are, weaving everyday memories, like her mother’s famous mac and cheese recipe or her contagious laugh, into symbols of ongoing presence. Grief, Rochelle suggests, isn’t an erasure. Love endures, even when the body does not.

Reimagining Grief

What makes the book especially powerful is how it reimagines the role of children in grief. Too often, they are assumed to be too young to understand. Rochelle flips that script, allowing children to become active participants in healing. She recalled a day when she was overwhelmed by her own sadness, only for her niece to call unexpectedly and ask, “Why are you crying? Don’t cry, you’re going to be okay.” In that moment, Rochelle allowed herself to be cared for, recognizing that healing is not a one-way street from adult to child, but can move in both directions. That intergenerational exchange is what Rochelle hopes her book will spark in other families. By opening up conversations that have long been avoided, she sees the possibility for collective healing not only for children, but for the adults who still carry the grief of their younger selves.

“There are a lot of Black women walking around with unresolved grief,” she admitted. “Writing this book helped heal a part of that in me.”

The strength of “Where Did Grandma Go?,” lies in its ability to meet readers wherever they are in their grief. For some, it may be the loss of a family member. For others, it could be the end of a relationship or a dream. Grief wears many faces, and Rochelle is reminding readers that silence only prolongs its weight.